Happy Hour Concert: Mozart’s Paris Symphony with Jonathan Cohen

Sponsored By

Sponsored By

(Duration: 17 min)

Desperate for a job away from his hometown of Salzburg, the 22-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart traveled with his mother to spend part of 1778 in Paris, a city that had adored him as a child prodigy. The only job lead he generated was for a post as an organist at Versailles, which he declined, and amid the professional disappointment, he faced personal tragedy when his mother fell ill and died.

One of the few bright spots in that dismal trip was a commission to compose a symphony for the Concert Spirituel, a series that featured one of Paris’ biggest and best-established orchestras. Active for more than fifty years by that point, the orchestra even had its own signature flourish, the premier coup d’archet: a unison bow-stroke at the start of a work that showed off the ensemble’s precision. Mozart used all the forces at his disposal in his “Paris” Symphony, writing for an unusually large orchestra that included clarinets. And he even incorporated the stereotypical coup d’archet at the start of his symphony, but this was perhaps a bit cynical, considering that Mozart wrote to his father, “These oxen here make such a to-do about it! What the devil! I can see no difference — they merely begin together — much as they do elsewhere.”

The symphony’s opening motive rises rapidly up the scale, a gesture that circulates throughout the first movement. In a sly moment of the development section, that scale-figure makes the shocking “mistake” of going a half-step too far. The Andante middle movement plays like a scene from a comedy of manners, with calm and courtly themes that pause politely to let each other speak. Forgoing a minuet and instead using the older three-movement pattern, the symphony proceeds directly to the finale that draws the listeners in with a scurrying piano start and then blasts a forte response. The contrapuntal treatment of the second theme foreshadows the famous fugal conclusion to Mozart’s last symphony, No. 41 (“Jupiter”), composed a decade later.

Aaron Grad ©2023

(Duration: 20 min)

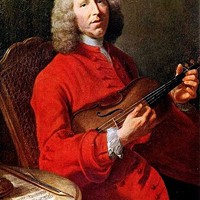

Before Jean-Philippe Rameau moved to Paris in 1722, he worked as a church organist in various small towns, and his only notable compositions were assorted vocal works and a book of harpsichord pieces. He soon published a groundbreaking harmony treatise and two more books of keyboard suites, paving the way for his greatest ambition, finally achieved at the age of fifty: to compose grand operas. He went on to create some thirty works for the stage, the finest by any French composer since Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Rameau’s first opera was Hippolyte et Aricie from 1733. Its overture begins in the stately style of Lully with the snapping rhythms of dotted notes, but the first sign of Rameau’s progressive approach appears in the fast section that follows with unusually dense and stormy counterpoint. In a plot typical for that period of obsession with Ancient Greece, the gods argue and intervene as mortals seek doomed love. The short instrumental number excerpted from the prologue served as entrance music for the forest inhabitants.

Rameau’s first opera followed the elevated format of the tragédie en musique, but he soon branched out into various forms of the opéra-ballet, a less serious genre of theater that made ample room for dancing and comedy. Naïs from 1749, for example, used a setting at the Isthmian Games to flesh out a love story between the god Neptune and the titular nymph. A seven-minute dance number, set to music in the cyclical form of a chaconne, pauses the plot to for a montage of wrestling, foot-racing, and the coronation of the victors.

Le temple de la Gloire (The Temple of Glory) from 1745 was another opéra-ballet on Greek themes, this one composed to celebrate victory in a major battle in the ongoing War of the Austrian Succession, using a libretto by the celebrated author Voltaire. The tender melody for the muses uses the pure tone of flutes and harp-like plucks to evoke those enchanting goddesses.

Rameau had plenty of detractors as he continued to push the boundaries of French opera, and the debate was at its fiercest around the time he presented his fifth opera, Dardanus, in 1739. Featuring a supernatural plot with countless twists and turns, this tragédie en musique was overflowing with sounds and ideas; as one contemporary reviewer quipped, “There is so much music that in three whole hours the orchestra didn’t have time so much as to sneeze.” Rameau made substantial revisions after the original production run of 26 performances ended, simplifying the plot and adding much new music that debuted with a second staging in 1744. In typical fashion, the opera ends with an extended ballet scene, including a Chaconne based on a recurring bass line. The rich orchestration spotlights the contrast between the string and wind sections.

Aaron Grad ©2023

Listen to Audio

Listen to Audio

(Duration: 21 min)

Franz Joseph Haydn became a court composer for Austria’s wealthy Esterházy family in 1761, and four years later he was put in charge of all the court’s vast musical activities. His patron, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, was an avid musician and a true supporter of the arts, but he kept his Kapellmeister on a tight leash, especially during the long stretches of time spent at an isolated summer palace where the musicians had to produce an endless stream of operas and other entertainment. Under those demands, Haydn later wrote, “I was forced to become original.”

In 1779, Haydn negotiated a new contract that gave him more leeway to compose and publish independently, and soon his music was attracting followers throughout Europe. One foreign admirer was a young French count, Claude-François-Marie Rigolet, who commissioned six symphonies that Haydn composed in 1785 and 1786. These “Paris” Symphonies earned Haydn the handsome sum of 25 louis d’or each, plus additional fees for publication. (By comparison, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart earned only 5 louis d’or for his “Paris” Symphony from 1778.)

Haydn’s “Paris” symphonies capitalized on the large orchestra employed for the Concerts de la Loge Olympique, conducted by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. In the Symphony No. 85, the slow introduction references the classic French overture with its majestic dotted rhythms and unison statements, details that show Haydn’s awareness of his intended audience. The Vivace body of the movement is a model of economy, with a small collection of themes that gain intrigue when placed in unexpected contexts, such as a surprise detour to F-minor on the way to the anticipated key of F-major.

The second movement Romanza was another local crowd-pleaser, with a set of variations on the French folksong La gentille et jeune Lisette. The Menuetto makes a game of chortling grace notes and offbeat accents, and its contrasting trio section strikes up the unlikely pairing of bassoon and violins over pizzicato. The same pairing returns to begin the Presto finale that bounds along with a particularly active and independent bass line. Queen Marie Antoinette purportedly loved this symphony the most of Haydn’s offerings for Paris, earning it the nickname “La Reine” (“The Queen”).

Aaron Grad ©2023

Happy Hour is from 4pm–6pm. Food Trucks will be on-site at 4pm.

Please stop by the box office to pick up your drink voucher(s) prior to attending the Happy Hour.

Beer provided by: La Doña Brewery

Food Trucks: VB&J’s/Sasquatch Sandwiches/Café Cairo/Montebello

Get driving directions and find nearby parking.

Find dining options close to the venue.

View seating charts to find out where you'll be seating.

SPCO concerts are made possible by audience contributions.

For exclusive discounts, behind-the-scenes info, and more:

Sign up for our email club!